Bill Shorten was, simply, Minister for the NDIS. Mark Butler, however, is now both Minister for the NDIS and Minister for Disability. Why the difference and does the change mean disability and the NDIS are now two different things?

A question like this might seem arcane, even meaningless, but in government words matter. Fit a definition correctly, and you qualify for money; fail and there’s none or it’s delivered differently. That’s why people are fascinated with Butler’s new title, which distinguishes between his role as Minister for Disability and Minister for the NDIS.

And while this might seem like a pointless debate, it actually carries real-world consequences. Particularly for people with disability.

At first glance the change appears semantic. Isn’t the NDIS just how the government supports people with disability? Well, no - and that’s the point. By giving Butler two separate titles, the government is subtly, but importantly, acknowledging “disability” and “the NDIS” are not the same thing. One is a whole-of-society issue. The other is a funding mechanism.

The first requires general programs provided and available to anyone. The second delivers specific services only for those who qualify.

Re-define disability like this, and you can see why the government might do it. There’s no need, for example, to test and deliver individualised programs to every young boy who might now qualify for the NDIS (currently 12.7 percent of boys between the ages of five and seven).

Instead government can establish other ways of coping with large cohorts of people with similar needs. Doing this might be a better way of dealing with a problem that shouldn’t necessarily be treated through programs created for each individual.

Dealing with the issues this way would also (and purely incidentally, of course) offer a much cheaper way of solving a huge and growing problem. How much better (and cheaper) to instead deal with these individuals as a group.

continue reading (from the newsletter) here:

Distinctions like this matter, especially inside the bureaucracy. Definitions drive decisions. If a person fits the definition for NDIS eligibility, they can access individualised support packages. Miss that threshold, and they’re left to rely on (what remains of) mainstream services. In effect, the bureaucratic label conditions are treated under determines not just how much help individuals receive, but also where that help comes from.

That’s why people are beginning to suspect that Butler’s dual title might be much more than just symbolic. It reflects a growing recognition that disability policy must go beyond the NDIS.

With just 650,000 participants, the scheme clearly reaches only a fraction of the estimated 4.4 million Australians with disability. The rest live in the vast grey zone of “outside the NDIS,” where services are fragmented and accountability is unclear.

This formulation reverses the old formula.

The problem is the reverse of the situation before the NDIS was created.

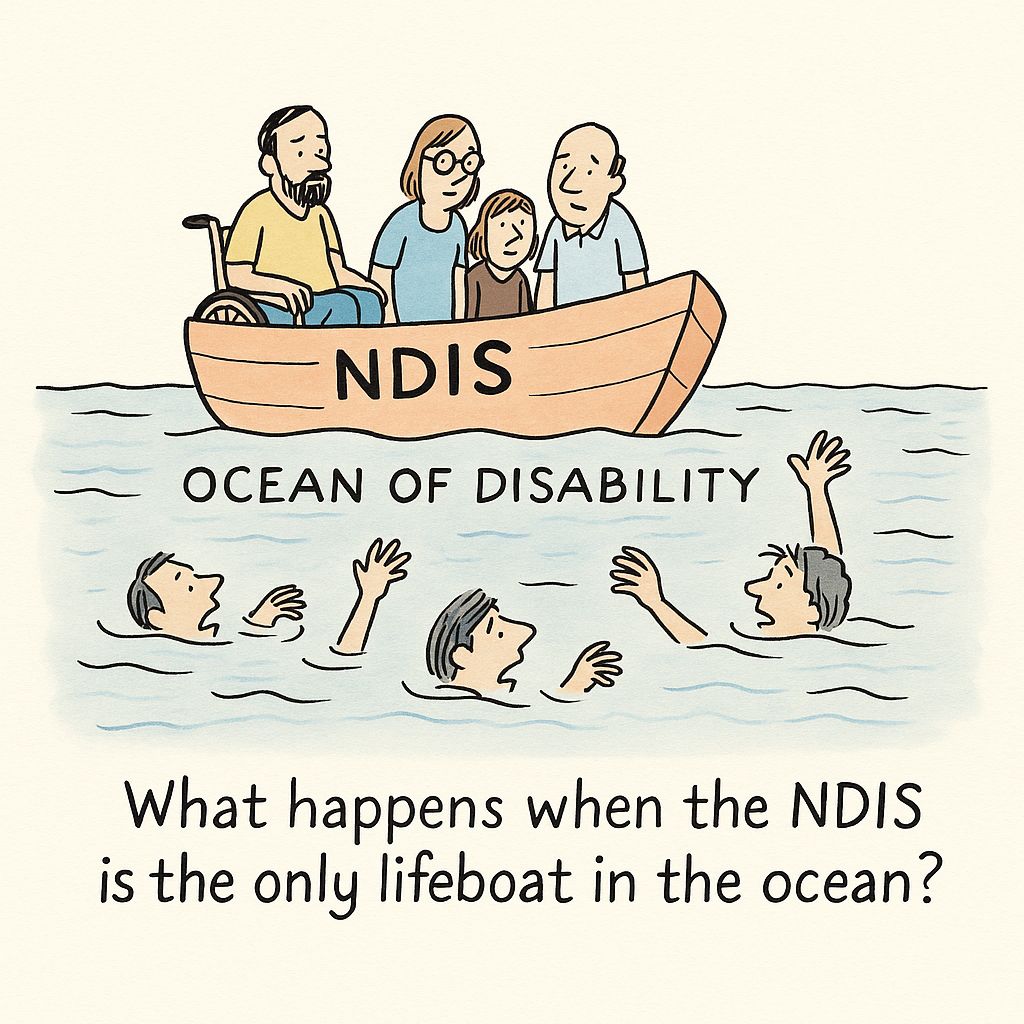

Today it’s the NDIS that is “the only lifeboat in the ocean” and everybody is attempting to scramble into it. The problem is there isn’t enough room for everyone, as the growing cost of the program demonstrates. By offering other ways of dealing with disability, government can offer other ways of helping individuals stay afloat.

Titles shape structures, structures shape funding, and funding shapes lives.

In this case, the fine print of a ministerial name change may signal a significant shift: treating disability as a whole-of-government responsibility.

It becomes just like ‘health’, or ‘education’. School programs aren’t created around each individual pupil, even though this might be a far better way of dealing with individual problems. Why should disability be any different?